Author: Jenna Christian

Geopolitical youth: Research on JROTC and military enlistment in Houston

T.E.J.A.S. Toxic Tour of Houston’s East End

#WhatHappenedtoSandraBland

December 2014: Black Lives Matter at the Houston Galleria Mall

Jan 23, 2017: Post-Election Actions

After seeing so many pictures this weekend from the Women’s March, I’m glad to now see so many articles and friends posting information about actions you can take TODAY–as well as advice on getting organized to keep this work going once. I decided to compile the things that are appearing in my feed. I’m working my way down the list myself.

Some of these require you to sign up for email notifications. I get that people hate mass emails filling your inbox, but sometimes they’re actually useful. Read them.

Actions to get yourself organized:

- Sign up for email notifications of new legislations in Congress. Go to congress.gov. Scroll to the bottom footer, and under “Ways to connect”, select “RSS & Email Alerts.” You’ll have to create an account, but you can then select to get notifications of bills in Senate and House, or to follow the actions of particular legislators (you might consider getting notifications about the votes of your own reps). [Time: 10 minutes]

- Find out who your STATE legislators are (the people in your state capitol): Visit http://openstates.org. Enter your address. See who your legislators are. Click on them. Copy down the address and phone numbers. Print them and hang them on your refrigerator or save them in your phone. Use often. [Time: 5 minutes]

- Find out who your representatives are in the US House of Representatives: http://www.house.gov/representatives/find/ Copy down the address and phone numbers. Print them and hang them on your refrigerator or save them in your phone. Use often. [Time: 2 minutes]

- Find out who your representatives are in the US Senate: https://www.senate.gov/senators/contact/ Copy down the address and phone numbers. Print them and hang them on your refrigerator or save them in your phone. Use often. [Time: 2 minutes]

- Sign up for Call Them In: This website will send you email reminders with tailored call scripts to speak to elected officials on specific legislation. http://www.callthemin.com/ [Time: 1 minute]

- Subscribe to wall-of-us.org: The website has 4 weekly acts of resistance that are useful. For example, Jan 24th there is a day of action on resisting the cabinet picks. If you’re looking for an action to do on a particular day, this is a good place. [Time: 1 minute]

- Sign up for email/text alerts from the Movement for Black Lives to receive notifications about actions near you and ways to get involved: https://m4bl.net/ [Time: 1 minute]

Immediate actions (some are Houston specific, others aren’t):

1. Respond to Paul Ryan’s Phone Poll about the Affordable Care Act: He’s hoping to hear overwhelming opposition to the ACA. Call (202) 225-0600. You’ll hear a recorded voice describe a few different issues that you might share you’re opinion on. Press two to voice your opinion on Obama’s health care plan. You’ll then hear the voice describing Paul Ryan’s plan to cut the ACA. Press 1 to support the continuation of the ACA. [Time: 2 minutes]

2. Demand that your elected officials protect DACA: “Call your congresspeople (http://www.house.gov/representatives/find/and http://www.senate.gov/…/contact…/senators_cfm.cfm…), call the White House (202-456-1414), call everyone you can think of, and say: “I am calling to demand that the President protect DACA and immigrant families. DACA has helped the lives of nearly 1 million immigrant youth who contribute to their families, communities, and our economy, and it should not be touched. The President must not sign any executive order that hurts Dreamers or immigrants more generally, who are the heart and soul of our country.” [Time: 15 + minutes–the more you call the better]

3. If you’re in Houston, call the Sheriff and Mayor TODAY about ending 287g: “URGENT MESSAGE: HOUSTON Friends, tomorrow/today (MONDAY) is looking very not good for immigrants across the country. I’m asking for your help to SHARE this message far & wide; and to call Sheriff Ed Gonzalez (713-755-3647 or 713-755-6044) & Mayor Turner (832-393-0800) as early as 8am — 1-10 times. Trump seems to be making his shit moves (as early as 9:30AM TODAY) and there’s no more time to waste. PLEASE HELP. #HTownIsHome#HereToStay” [Time: 15 + minutes–the more you call the better]

4. Submit a public comment on Standing Rock to those preparing the Environmental Impact Statement on the Dakota Access Pipeline: Follow this link: https://sierra.secure.force.com/actions/National?actionId=AR0066309&id=70131000001Do2iAAC&ddi=N17ASAFB09&utm_medium=cpc&utm_source=facebook&utm_campaign=emacq&utm_content=nodapl_comment_v2. Fill in your info. Personalize the message if you can. You’ll be added to a Sierra Club email list, but you can remove yourself after. [Time: 3 minutes]

5. Keep checking back on the Women’s March List of 10 actions to take after the march: Go to https://www.womensmarch.com/100. The first action is easy: print a postcard and write to your senator. I’m sure you could just write a regular letter/postcard too, minus the Women’s March template stuff. [Time: 15-30 minutes]

6. If you’re white and aren’t already doing this, take some time today to learn about the problems with the Women’s March: Read articles about the experiences and feelings of Black, Brown, and other people of color about the Women’s March—not to mention transgender women. (Be wary of rallying calls and protest signs that essentialize womanhood in ways that exclude transgender women). Hopefully we agree the March was not enough—we’re going to have to do some much more difficult work than showing up at a rally. Time for us white people to deal with our shit and do this work better. Here are some articles about this that crossed my feed today [Time: just keep doing this all the time]:

http://www.joojooazad.com/2017/01/keep-your-american-flags-off-my-hijab.html

https://www.good.is/articles/seeking-solidarity-at-the-womens-march-in-washington

7. If you’re in Houston, consider attending and speaking at the City Council’s Public Comment Session: They are usually held at 1:30pm on weekdays. This would be a good place to voice opinions on 287g. There are more details about dates, times, and how to sign up to speak here: https://www.facebook.com/events/227047381085173/ [Time: Plan a few hours, I believe]

8. Sign another petition to the whitehouse.gov to release Trumps taxes: https://petitions.whitehouse.gov/petition/immediately-release-donald-trumps-full-tax-returns-all-information-needed-verify-emoluments-clause-compliance [Time: 2 minutes]

Feminist Discussion Post 2: The Wage Gap, Intersectionality, and the White Privilege of Liberal Feminism

(This post is the second in a discussion between Lauren Southern and I about feminism. The discussion emerged after Lauren posted a video about why she is not a feminist, to which I wrote an open letter to Lauren in response. Lauren and I then agreed to take part in the call-and-response style discussion, in which we post questions/prompts for one another to reply to. Lauren is posting her replies as videos on youtube, while mine are hosted here on this blog. Follow the links below for a complete history of the discussion, particularly #3, which describes in greater detail the format for this conversation and some of my thoughts about it.

Conversation history

- Lauren’s original video “Why I’m not a Feminist”

- My response “A reply to Lauren Southern’s “Why I’m not a Feminist””

- Announcement about the virtual discussion

- My first prompt for Lauren “Feminism, the devaluation of the feminine, and men”

- Lauren’s first post to me “Feminism Discussion Part 1”)

Hi Lauren,

Thanks for your response to my first post. (I’m embedding the video of your first reply below so others can view it in the context of this discussion). Sorry it has taken me a few days to reply.

So, before I move to addressing your prompt for me regarding the wage gap, I want to follow up on some of the points you raised in your video reply to my prompt. I think some of the points I was trying to communicate in my prompt for you were either insufficiently explained by me or misunderstood by you, and I just want to be sure we are on the same page about what I’m actually asserting with regard to feminism before we move forward. I’ll just bullet out the key points. For those that want to skip ahead to the discussion of the wage gap, intersectionality, and white privilege in liberal feminism, I’ve delineated where I start talking about that.

RESPONSE PART 1: Clarification of last post

- Are all of women’s issues taken care of? Early in your most recent video, you say that past feminist waves have already addressed all the issues in women’s lives. Frankly, this is really troubling if you in fact believe it. I’m not sure you do believe it though, since later in your reply you refer to women’s problems when you suggest women could address their issues by acting more masculine (I’ll address that a little later), and at the end of the video you refer abstractly to “the real problems both genders have.” I’m going to give you the benefit of the doubt, therefore, and assume that you do believe women still face unique inequalities and problems in their lives (particularly, if you think about women’s experiences intersectionally and transnationally). However, if I’m wrong and you do believe that all issues facing women have been addressed (and thus you presumably believe that men are the only ones facing gendered issues), perhaps we can discuss that in the next round.

- Did I say all men need to be more feminine? You seem to have taken from my last post that my goal is to make men more feminine. This is not what I argued. What I was saying is that the devaluation of things that are deemed feminine (e.g. emotions) hurts

both men and women. Even in your original video, you argue that men are hurt when they are ridiculed for not being “manly enough”, and the examples you cited for things that put men in harms way are deeply linked to gendered norms of acceptable masculinity. Rigid expectations about gendered behavior foreclose options, and in some cases they help produce male injury and death (for example, in relation to male suicide, where expressing and seeking help for emotional distress is often seen as shameful and feminine). Thus, the goal is not to say that men need to be more feminine, but rather to say that men (and women) should be not have to embody rigidly defined norms of masculinity in order to be deemed intelligent, worthy, productive, strong, or so on. It should be socially acceptable (even healthy) for men and women to embody a whole range of behaviors and characteristics. For men, this includes those deemed feminine, like being nurturing or expressing emotion. You say, “Feminism’s goal is not to fight for equal rights between men and women, but instead to make men more feminine.” Feminism is about equal rights between men and women. It is also about the equal valuation of femininities and masculinities (there are certainly multiple forms of both), and the freedom for both men and women to embody these in ways that they feel comfortable with.

both men and women. Even in your original video, you argue that men are hurt when they are ridiculed for not being “manly enough”, and the examples you cited for things that put men in harms way are deeply linked to gendered norms of acceptable masculinity. Rigid expectations about gendered behavior foreclose options, and in some cases they help produce male injury and death (for example, in relation to male suicide, where expressing and seeking help for emotional distress is often seen as shameful and feminine). Thus, the goal is not to say that men need to be more feminine, but rather to say that men (and women) should be not have to embody rigidly defined norms of masculinity in order to be deemed intelligent, worthy, productive, strong, or so on. It should be socially acceptable (even healthy) for men and women to embody a whole range of behaviors and characteristics. For men, this includes those deemed feminine, like being nurturing or expressing emotion. You say, “Feminism’s goal is not to fight for equal rights between men and women, but instead to make men more feminine.” Feminism is about equal rights between men and women. It is also about the equal valuation of femininities and masculinities (there are certainly multiple forms of both), and the freedom for both men and women to embody these in ways that they feel comfortable with.

- Is gender natural? This is a place where we clearly disagree. You argue that it is an “obvious fact” that men are naturally/biologically more aggressive, competitive, visual-spatial, sexual and driven. This is by no means an “obvious fact”, however, nor is it “lazy” or “pseudo intellectual” (as you say) to discuss the ways that gender is learned. That’s actually a pretty dismissive and insulting treatment of an incredibly large body of work by generations scholars and researchers. There has been a lot of work (by feminists and non-feminists alike) that debunk the assertion that gender is essential and determined by biology. Yes, we have material bodies, but they do not determine who we are, how we behave, or how we identify ourselves. Thus, the meaning we make of bodies and how we are taught (and decide) to use our bodies is deeply social. Just look take a stroll down the children’s toy aisle, and you will witness the early reproduction of gender norms. Boy’s toys encourage action, creative building, strength, and aggression, while girls toys teach beauty, the importance of male attention and protection, and how to perform domestic responsibilities like childcare, cooking, cleaning, and decorating. These lessons extend well beyond the toy aisle though, and we learn, interpret, and perform our gender in relation to norms taught in our homes, schools, media, and everyday interactions. Moreover, your argument that men are naturally aggressive, competitive, and sexual (in contrast to women) actually helps to produce the very narratives that you yourself are trying to challenge–for example, the problematic narrative that men are natural aggressors (not victims). These narratives have also helped to make certain violences like rape seem natural, as people assert that “boys will be boys” and “they just can’t help themselves, it’s in their nature.” Finally, your assertion of the biological essentialism of these gendered behaviors undermines your own argument that women could achieve success by just acting more masculine. When you say women can learn to be more masculine, you too are acknowledging that much of these supposedly natural behaviors are social, learned, and thus alterable.

- Proof that feminists speak on men’s issues? You say that I provide no proof that feminists speak for men’s issues. This is a bit confusing, since my last two posts have been filled with citations of feminists speaking on men’s issues.

- Do the top issues for feminist in 2015 pertain only to women? This is something you claim in your video, and you offer two sources (1 and 2) to support your claim. While I don’t think that feminist issues can be reduced to these lists given the breadth and diversity of the field, the fact is, when you examine these links there are actually plenty of issues that speak to men. In the first article, you see Janet Monk calling for coalitions with other racial justice and LGBT movements, which include men of color, and gay, bisexual, and transgender men. Lux Alptram similarly calls for the inclusion of gender non-conforming people and people of color, which will include men. Ai-jen calls for a livable wage and quality care for working families, which again would include men. Elizabeth Nyamayaro calls for solidarity between men and women, creating “a shared vision of gender equality that benefits all of humanity.” Jessica Pierce, Charlene Carruthers, Patrisse Cullors, Opal Tometi, and Mikki Kendall all call for a focus on police violence against black people–a movement that has gained particular momentum recently in response to state violence against black men (although women do face much police violence too). Tometi’s call also includes detention and deportation issues, which affect men. Lindy West and Alexandra Brodsky call to protect victims of assault, and both are gender neutral in their call. And, Mia McKenzie points to issues of queer and trans people of color–again she does not limit this to women (and the website she curates regularly includes articles by men and about men’s experiences). The second article you cite also includes family leave and paternal leave policies that pertain to men, although I have to say I see a lot of this second article as indicative of some of the problems with liberal feminism that I will describe in the discussion about the wage gap. Stay tuned for that though.

- Are most feminists really misandrists who want men to die? Do I represent the fringe? According to you most feminists are misandrists who want men to die, and in contrast, my (non-man-hating) approach to men is representative of the fringe of feminism. I’m really do not understand where you’re getting this from. I have been studying feminist theory and been engaged in discussions with feminist scholars and activists for years, and I have never once met or read a single feminist who said they wanted men to die. Not one. I also haven’t heard feminist “rage” about women wanting to walk around naked either, yet you claim these are the “most active and vocal” feminists. In contrast, you say that the feminism I subscribe to “is not widely practiced” and is a “fringe version”. What do you base this on? I could literally cite hundreds and hundreds of feminists both inside and outside of the academy that describe feminism in relatively similar ways as I have, but I cannot cite a single feminist who wants men to die or who is deeply invested in women being able to walk around naked.

- I’m sorry you’ve been jeered and ridiculed in replies to your video. Trust me, I’ve gotten the same, as I’m sure you know if you’ve read comments on my blog (or even those comments directed to me on your video). I’m not complaining too much. What I’ve gotten is nothing compared to other feminist bloggers, who receive a daily barrage of people saying they should die, that they deserve to be raped, or other cruel and violent things. People on the internet can be truly awful to one another. Now, that being said, one of your complaints was that feminists said your original video was anti-feminist and anti-equality. I have to say, I do think the characterization of your video as anti-feminist is arguably pretty fair. You have been vocal in your distaste for and dismissal of feminism. On the matter of equality, I do actually believe that you desire and believe in equality, but I have deep reservations and concerns about the anti-equality outcomes that emerge through some of your positions. My guess is that you would probably say the same about me on the topic of equality. By now, it seems clear we have different ideas about what equality looks like and how it is made, which is perhaps something we could talk about.

———————

RESPONSE PART 2: Reply to your question about the wage gap

Alright, now onto your question. Again, it’s easiest for me to organize my reply as a list, so here goes.

1. You say the wage gap is a “feminist myth”.

It is not only feminists who document and analyze the wage gap, and it cannot be simplified to an issue invented by feminists. In fact, a review of just some of the most recent literature on the matter reveals an overwhelming consensus on the existence of a gendered wage gap (AAUW 2015; Aizer 2010; Alon and Haberfeld 2007; Bastos et al 2009; Briggs 2011; Broyles and Fenner 2010; Budig and England 2001; Campbell and Pearlman 2013; Carrillo Hemmeter 2008; Cech 2013; Cho 2007; Christofides et al 2013; Daczo 2012; Daly et al 2006; Day 2012; Diaz and Sanchez 2013; Douglas and Steinberger 2015; Dozier 2010; Elmelech and Lu 2004; Fisher and Houseworth 2012; Flippen 2014; Franks 2007; Glauber 2008; Hirsch 2008; Hoyos et al 2012; Ioakimidis 2012; Kassenboehmer and Sinning 2014; Kennedy et al 2009; Kim 2013; Kunze 2005, 2008; Liu 2004; Livanos and Pouliakas; Machin and Pahani 2003; Maume and Ruppaner 2015; McDonald and Thorton 2011; McGee et al 2015; McGregory 2013; Mishel et al 2014; Misra and Murray-Close 2014; Monk-Turner and Turner 2004; Neal 2004; Nyhus and Pons 2012; Palomino and Pevrache 2010; Pastore and Verashchagina 2005; Penner 2008; Renzulli et al 2006; Sabir and Aftab 2007; Schulze 2015; Smith and Glauber 2013; Vera-Toscano et al 2004). And, I should note that only a couple of those scholars identify as feminist or even mention the word “feminism” in their work.

We definitely need to break this down and talk a bit about what all these people are saying. Before we do that, however, we clearly need to get on the same page about what the wage gap is since your definition is much more narrow than its standard definition. The American Association of University Women (AAUW) has a really user-friendly definition, and I assure you their definition is representative of the way most scholars (including those cited in the articles you offer) define it as well. According to the AAUW, “The pay gap is the difference in men’s and women’s median earnings, usually reported as either the earnings ratio between men and women or as an actual pay gap.” So, the wage gap does not refer only to gaps in wages for “the exact same job, with the same seniority and education”, as you describe. The pay gap is a term that more broadly encompasses the uneven earnings of men and women. Now, that being said, as Briggs (2011) writes, “research consistently shows individuals doing the same, or comparable work, are not getting paid the same.”

2. The role of choice in shaping the gender wage gap.

So, in thinking about our definition of the wage gap, there are multiple approaches to understanding and explaining it. Many talk about the wage gap using theories of human capital. These people examine the wage gap as a function of characteristics of the worker: unequal education, training, skills, personal choice of occupation, or personality. This is the camp you seem to fall into, since you argue, “men are paid more than women because of their choices.” It’s important to note that this human capital approach is not a denial of the existence of the wage gap however; rather they are just explaining it in a particular way.

In fact, feminist (and non-feminist) interventions into the wage gap often deal with addressing the structural ways that gender norms (not just overt gender discrimination) help produce these outcomes. For example, they discuss how gender ideologies work to route women towards particular jobs, and how occupational sorting impacts the pay gap (Penner 2008). They discuss how women’s uneven childcare responsibilities impact their choice of occupation and ability to advance their career, a pattern that has been dubbed the “motherhood penalty” (Budig and England 2001)—in contrast to evidence that men actually earn a wage premium for fatherhood (Glauber 2008). They also demonstrate how the norms of acceptable gender behavior influence confidence and negotiation stills (Nyhus and Pons 2012; Palomino and Peyrache 2010). As Misra and Murray-Close (2014) argue, the argument that the wage gap is solely a matter of choice and thus no policies are needed to address it is representative of “widespread confusion about the sources of the gender pay gap and a failure to appreciate the extent to which contextual factors, including policy supports for pay equity, condition the impacts of men’s and women’s choices on their earning.” Further, as the AAUW (2015) describes, even though women are more likely to go into disciplines like teaching that are paid less, we still should be asking questions about whether lower wages in female-dominated fields are fair. In this regard, perhaps it’s also worth considering how the gender composition of certain labor fields has also contributed the way that the labor is valued, as fields like teaching are often treated as reproductive labor akin to childrearing (going back to my previous discussion about productive/reproductive labor).

Ultimately, choice is far more complicated than you are acknowledging. One of the problems with this type of faith in a meritocracy (the idea that anyone can be successful if they make good choices and work hard) is that it can lead you to turn a blind eye to the systemic conditions that help produce certain outcomes. In this case, it is leading you to ignore how gendered social systems help produce gendered outcomes in wages, and the ways these outcomes distinctly impact people of color and other marginalized groups (as I discuss in a minute). I’m not saying these systemic conditions wholly determine futures, but dismissing them only allows us to see half of the story. Moreover, it allows us to unproblematically blame people (in this case, women) for their position, rather than critically and compassionately examining the systemic factors that might lead people down certain paths or to make certain choices.

3. When all things are equal, the gender wage gap still persists.

There is ample evidence that even when you account for occupational sorting, education, and skills the wage gap cannot be explained away. Analyzing data from the US Census, the Department of Education, and the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the AAUW describes how, even after “accounting for college major, occupation, economic sector, hours worked, months unemployed since graduation, GPA, type of undergraduate institution, institution selectivity, age, geographic region, and marital status”, there is still a 7 percent earning gap between men and women college graduates that is unexplained a year after graduation. Ten years after college graduation, there is a 12 percent difference in earnings. Many studies demonstrate the persistence of wage gaps even when controlling for key “human capital” variables (e.g. Briggs 2011; Chech 2013; Daly et al 2006; Kim 2013; Machin and Pahani 2003; Misra and Murray-Close 2014; Schulze 2015; Weinberger and Joy 1997).

4. Feminist theories of intersectionality are essential in understanding the wage gap.

A review of the literature on the wage gap makes it clear how important it is to distinguish which women we are talking about. Women’s experiences are not universal, and the wage gap does not operate the same way for women in every pay scale, in every discipline, or in every country or region, and it certainly does not operate the same way across race, age, class, or sexuality. As Smith and Glauber (2013) write, “Inequality between women and men has decreased over the past four decades in the US, but wage inequality among groups of women has increased.” The wage gap must be examined intersectionally. Let’s look at a few indicators of this.

Alon and Haberfeld’s (2007) study of work history data reveals “constant racial and ethnic wage gaps among women with college education and a widening race gap among women with no college degrees.” They continue, “minorities earn less even in comparison to Whites with similar levels of education.” The existence of a racial wage gap is also well established in the literature, as the skills of people of color (even when they are equal to those of white people) are less valued. Broyles and Fenner (2010; see also Fryer et al 2013; Heywood and Parent 2012; Kennedy et al 2009; Kerr and Walsh 2014; Lyons and Pettit 2011; Mason 2011; McGregory 2013; O’Gorman 2010) review the ways that hiring has consistently found evidence of racial discrimination, with studies suggesting white preference rates ranging from 50 to 240 percent higher than for black candidates. On the whole, white people spend less time looking for jobs and less time unemployed, they tend to get more stable jobs, and are offered higher wages. As Dozier (2010) finds examining the period from 1980 to 2002, “Although the transition to an “office economy” rewarded both black and white women with wage gains, white women reaped greater benefits.” And, while women of each racial group in the US are more likely to be poor than men of their same origin, “white women are less likely to be poor than minority-status men” (Elmelech and Lu 2004). Similar inequalities are found between white and Latina women (Carrillo Hemmeter 2008; Flippen 2014; Rodriguez and Devadoss 2014).

Alon and Haberfeld’s (2007) study of work history data reveals “constant racial and ethnic wage gaps among women with college education and a widening race gap among women with no college degrees.” They continue, “minorities earn less even in comparison to Whites with similar levels of education.” The existence of a racial wage gap is also well established in the literature, as the skills of people of color (even when they are equal to those of white people) are less valued. Broyles and Fenner (2010; see also Fryer et al 2013; Heywood and Parent 2012; Kennedy et al 2009; Kerr and Walsh 2014; Lyons and Pettit 2011; Mason 2011; McGregory 2013; O’Gorman 2010) review the ways that hiring has consistently found evidence of racial discrimination, with studies suggesting white preference rates ranging from 50 to 240 percent higher than for black candidates. On the whole, white people spend less time looking for jobs and less time unemployed, they tend to get more stable jobs, and are offered higher wages. As Dozier (2010) finds examining the period from 1980 to 2002, “Although the transition to an “office economy” rewarded both black and white women with wage gains, white women reaped greater benefits.” And, while women of each racial group in the US are more likely to be poor than men of their same origin, “white women are less likely to be poor than minority-status men” (Elmelech and Lu 2004). Similar inequalities are found between white and Latina women (Carrillo Hemmeter 2008; Flippen 2014; Rodriguez and Devadoss 2014).

Further, just as feminism is a transnational movement, so too is the gender wage gap also a transnational issue. Gender wage gaps are documented in Portugal (Bastos et al 2009), Korea (Cho 2007), Honduras (Hoyos et al 2012), Czech Republic (Ioakimidis 2012), Vietnam (Liu 2004), Greece (Livanos and Pouliakas 2012), South Korea (Monk-Turner and Turner 2004), Belarus (Pastore and Verashchagina 2005), Pakistan (Sabir and Aftab 2007), the UK (Schulze 2015), across the European Union (Christofides at al 2013), as well as in other comparative international studies (e.g. Daly et al 2006; Diaz and Sanchez 2013; Machin and Pahani 2003).

The gender wage gap also varies between major metropolitan areas and nonmetropolitan areas, where women suffer more of a gap (Smith and Glauber 2013; Vera-Toscano et al 2004). It varies from state to state. It unevenly impacts people who are gay or lesbian (Douglas and Steinberger 2015; Elmslie and Tebaldi 2014). It impacts non-unionized women of color more than unionized women of color (McGregory 2013). And it varies between high-income men and women and low-income men and women (Kassenboehmer and Sinning 2014; Mishel et al 2014; Shannon 1996).

Therefore, the gender wage gap cannot be understood just through gender. It must be understood and confronted intersectionally with attention to context.

5. You say the wage gap “has been disproved many times before”.

First, you’re overshooting the mark a bit here. Even the sources you yourself cite don’t say the gap has been disproved. They say that it has narrowed, or they question one specific statistic used to measure it (the often-cited 23-cent pay gap figure). As Kunze (2008) describes, “There is no undisputed method for measuring the gender wage gap,” and this leads to different interpretations about it’s size and operation (particularly when it’s examined intersectionally). The consensus (even among those you cite), however, is that it still exists.

Take the Time article by Christina Hoff Sommers that you cite as an example. She is taking issue with the one statistic. She says “the 23-cent gender pay gap is simply the difference between average earnings of all men and women working full-time. It does not account for differences in occupation, positions, education, job tenure or hours worked per week. When such relevant factors are considered, the wage gap narrows to the point of vanishing.” Alright, yes, the 23-cent statistic does not control for all those factors. As I’ve described already, however, this does not make this statistic irrelevant or unimportant, and it reflects the accepted definition of what the wage gap is. Now, her claim that it narrows to the point of vanishing is a bit suspect. First, we again need to be vigilant to the question of which women we are talking about. Feminists do not treat women as a universal block, and the gap is variously narrow or wide depending on who you are referring too. Second, when we take a look at her sources, their “decisiveness” is a bit more muddy than she claims. She refers to the decisive evidence from economists, and she cites one report by CONSAD research corporation to support her claim. Aside from the fact that one study alone isn’t decisive evidence, if you examine their report you’ll find they describe problems of insufficient data and the need for more research on the matter. Moreover, their argument isn’t not even that the wage gap doesn’t exist, it’s that they believe much more of it can be explained by the human capital model of thinking than others acknowledge. The additional two sources Sommers offers as evidence that the wage gap has been debunked are both articles that she herself wrote, which again rely largely on the same CONSAD study. She also claims that the AAUW has debunked the gender wage gap, which if you actually read any of the AAUW reports is plainly false. In fact, their extensive studies (1, 2) reveals quite the opposite.

Needless to say, your claim that the wage gap has been debunked many times before has a handful of problems: 1) it relies on a warped definition of what the pay gap actually is, 2) it takes arguments about the relative role of human capital and extends them in ways that the original researchers are not actually advocating, 3) it over-extends an explanation of the factors shaping of one statistic to claim that the wage gap doesn’t exist at all, and 4) it relies on a small sample of research and characterizes it as decisive, despite those authors own acknowledgement of the incompleteness of their data and findings.

6. You say feminists argue that women aren’t welcome in higher paying STEM fields when women are in fact favored two-to-one in them.

A couple points in reply to this.

- The all three (1, 2, 3) of the sources you cite for this claim are in reference of the exact same study by Williams and Ceci, so this isn’t exactly overwhelming evidence. Particularly since one of the articles you offer also quotes other well-established scholars describing reasons to be suspicious of their methods and findings. This should make us at least be cautious about their finding, and necessitates that we temper claims about the decisiveness of their research.

- As many other researchers have argued, you cannot extrapolate what happens in one field to assume this is the case in all fields. Williams and Ceci’s claim that their study on STEM indicates that “anti-female bias in academic hiring has ended” is frankly academically irresponsible. They step back on this claim a little in a follow up question when they clarify that they aren’t saying women don’t face discrimination, and they agree the paper doesn’t demonstrate that the problem is solved.

- The calls in the article to focus on things beyond overt discrimination are actually quite in line with feminist efforts to increase women’s representation in STEM—for example, by getting girls interested in science at a younger age, challenging ideas that science is masculine, etc.

- Williams and Ceci’s claim in their abstract that the under-representation of women is typically attributed to sexist hiring is just not true. Sexist hiring is just one among many things it is attributed to, including gendered pipelines towards certain disciplines that start at young ages, perceptions/realities of institutional cultures, etc. Feminists argue that gendered outcomes often have gendered origins, even if overt sexist discrimination is not the cause.

7. You point to one incident with Sarah Silverman to characterize all feminists as dishonest.

Look, I don’t know what was up with the Sarah Silverman situation. Maybe she was being manipulative and dishonest, maybe she didn’t remember the incident well, maybe there was a miscommunication between her and the club manager about what she would be getting paid. I don’t know. The point is, even is she was being totally dishonest, it is wholly unfair to use that as evidence that feminists at large are desperately conspiring to make up wage gaps “to keep their narrative going”. There is plenty of evidence that wage gaps persist, particularly if you look at them intersectionally. Using one person’s dishonestly to justify dismissing all claims is ridiculous.

Look, I don’t know what was up with the Sarah Silverman situation. Maybe she was being manipulative and dishonest, maybe she didn’t remember the incident well, maybe there was a miscommunication between her and the club manager about what she would be getting paid. I don’t know. The point is, even is she was being totally dishonest, it is wholly unfair to use that as evidence that feminists at large are desperately conspiring to make up wage gaps “to keep their narrative going”. There is plenty of evidence that wage gaps persist, particularly if you look at them intersectionally. Using one person’s dishonestly to justify dismissing all claims is ridiculous.

8. You ask why feminists keep talking about this “invisible problem” “instead of dealing with some of the real problems that both genders face.”

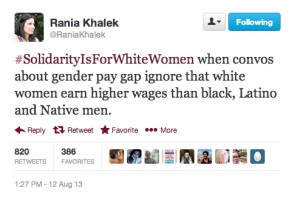

First, I hope I’ve addressed enough by now the ways that wage gaps persist as a problem. Second, I’m glad you’re acknowledging here that there are real problems facing women too, in contrast to your earlier statement that First and Second Wave feminism had already solved everything for women. Finally, the question of “why wage gaps” and not other issues is actually totally in line with my own concern and the concern of other feminists about the focus on the issue, particularly when you consider how work on the gender wage gap has tended to unevenly benefit white women. Feminists who focus largely on the wage gap, while ignoring systemic issue of racial inequality, poverty, and imperialism, for example, need to think more critically, and this is where I want to turn to a discussion about white privilege and liberal feminism in relation to wage battles…

The white privilege of liberal feminism

It’s interesting that you took from my earlier article that I was deeply invested in the debate about the wage gap, particularly after I said in the announcement of this discussion that I would rather talk about the current situation of police violence than the wage gap. I mean, by now it should be obvious that I do believe gender wage gaps exist and matter. However, most efforts to address the wage gap have unevenly helped white women, as they have been the primary beneficiaries of increased access to higher education and higher salaries. As bell hooks writes, the reality is “that privileged white women often experience a greater sense of solidarity with men of their same class than with poor white women or women of color.” In this regard, giving some women more access to higher wages doesn’t do much to challenge the broader social and economic structures that produce so much inequality for so many people. In other words, it leaves structural racism and poverty unchallenged.

The issue of the wage gap is a good marker of the difference between liberal feminism and radical feminism. The word “liberal” here is not in reference to the common dichotomy of liberal versus conservative. Liberal feminists focus on how women can gain equality through existing structures of liberal democracy and market capitalism. Key liberal feminist goals would be to gain equal political representation (without challenging the existing political system), or equal pay (without challenging the existing economic system). While being a prominent form of feminist scholarship and activism, liberal feminism is often critiqued by feminists of color, postcolonial feminists, and socialist/Marxist feminists (among others) for its individualism and its failure to challenge existing societal structures that produce inequality (of which the law and the economy are at the forefront). Thus, feminists debate extensively about whether equality can be created through liberal feminism, and the issue of women’s equal membership in an unequal economic system is a prime example.

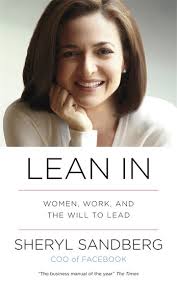

In her discussion of Sheryl Sandberg’s best-selling book Lean In, feminist icon bell hooks describes the issue far more eloquently than I could, so I’m going to quote her heavily here. In Lean In, Sandberg describes how women can climb the corporate ladder and gain leadership if they just have the courage to ‘lean in’ and persevere. In a sense, Sandberg is making an argument similar to the one you made, Lauren, (although she does call herself a feminist), that if women just play by the gendered rules of masculinity, they could overcome inequality. Here, hooks’ concerns about Sandburg’s message could be also be offered as a reply to your message about choice and the wage gap: “It almost seems as if Sandburg sees women’s lack of perseverance as more the problem than systemic inequality. Sandburg effectively uses her race and class power and privilege to

In her discussion of Sheryl Sandberg’s best-selling book Lean In, feminist icon bell hooks describes the issue far more eloquently than I could, so I’m going to quote her heavily here. In Lean In, Sandberg describes how women can climb the corporate ladder and gain leadership if they just have the courage to ‘lean in’ and persevere. In a sense, Sandberg is making an argument similar to the one you made, Lauren, (although she does call herself a feminist), that if women just play by the gendered rules of masculinity, they could overcome inequality. Here, hooks’ concerns about Sandburg’s message could be also be offered as a reply to your message about choice and the wage gap: “It almost seems as if Sandburg sees women’s lack of perseverance as more the problem than systemic inequality. Sandburg effectively uses her race and class power and privilege to  promote a narrow definition of feminism that obscures and undermines visionary feminist concerns.” Thus, uncritical narratives of “choice” and “meritocracy” erase the undergirding structures that shape the landscape within which one is able to “choose.” In other words, the narrative about the choice to lean in erases how these structures are distinctly raced, classed, gendered, euro-centric, and heteronormative. “To women of color young and old, along with anti-racist white women, it is more than obvious that without a call to challenge and change racism as an integral part of class mobility she is really investing in top level success for highly educated women from privileged classes.” (As another example, we saw concern about this emerge in response to Patricia Arquette’s recent Oscar acceptance speech where she called for gay people and people of color to support women’s efforts for equal pay. Here is a good elaboration of the white privilege that her statement reflected. She got some deserved flack from anti-racist feminists on this.)

promote a narrow definition of feminism that obscures and undermines visionary feminist concerns.” Thus, uncritical narratives of “choice” and “meritocracy” erase the undergirding structures that shape the landscape within which one is able to “choose.” In other words, the narrative about the choice to lean in erases how these structures are distinctly raced, classed, gendered, euro-centric, and heteronormative. “To women of color young and old, along with anti-racist white women, it is more than obvious that without a call to challenge and change racism as an integral part of class mobility she is really investing in top level success for highly educated women from privileged classes.” (As another example, we saw concern about this emerge in response to Patricia Arquette’s recent Oscar acceptance speech where she called for gay people and people of color to support women’s efforts for equal pay. Here is a good elaboration of the white privilege that her statement reflected. She got some deserved flack from anti-racist feminists on this.)

As hooks describes, feminism does not begin and end with the notion that it’s all about gender equality within the existing social system. I’ll conclude with her words:

“Importantly, whether feminist or not, we all need to remember that visionary feminist goal which is not of a woman running the world as it is, but a woman doing [her] part to change the world so that freedom and justice, the opportunity to have optimal well-being, can be equally shared by everyone—female and male.”

The end.

My prompt for you, Lauren

I think that I’ve written enough in this essay for you to reply without me posing a new question. So, in order to keep the conversation manageable, I’ll leave it open for you to respond however you want. Feel free to follow up on things I’ve said here, or pose new topics for discussion. As you may have gathered by my slow reply, the time commitment of writing these replies had ended up being more than I anticipated. With that in mind, I propose that we keep the conversation going, but allow it to happen at its own pace. What do you say?

All the best,

Jenna

References:

Aizer, A. (2010). The Gender Wage Gap and Domestic Violence. American Economic Reivew. 100: 1847-1859.

Alon, S. and Y. Haberfeld. (2007). Labor Force Attachment and the Evolving Wage Gap Between White, Black, and Hispanic Young Women. Work and Occupation. 34(4): 369-398.

Bastos, A., S.F. Casaca, F. Nunes, J. Pereirinha. (2009). Women and poverty: A gender-sensitive approach. The Journal of Socio-Economics. 38: 764-778.

Briggs, A.L. (2011). The Wage Gap Revisited: An Investigation of Salary Request Differences Among Black-White and Male-Female Workers. Dissertation. DePaul University.

Broyles, P. and W. Fenner. (2010). Race, human capital, and wage discrimination in STEM professions in the United States. International Journal of Sociology. 30(5/6): 251-266.

Budig, M.J. and P. England. (2001). The Wage Penalty for Motherhood. American Sociological Review. 66(2): 204-225.

Campbell, C. and J. Pearlman. (2013). Period effects, cohort effects, and the narrowing gender wage gap. Social Science Research. 42: 1693-1711.

Carrillo Hemmeter, M.S. (2008). Hispanic-White Women’s Wage Differentials. Dissertation. University of California-Davis.

Cech, E. (2013). Ideological Wage Inequalities?: The Technical/Social Dualism and the Gender Wage Gap in Engineering. Social Forces. 91(4): 1147-1182.

Chappel, M. (2012). Reagan’s “Gender Gap” Strategy and the Limitations of Free-Market Feminism. Journal of Policy History. 24(1): 115-134.

Cho, D. (2007). Why is the gender earnings gap greater in Korea than in the United States? Journal of Japanese International Economics. 21: 455-469.

Christofides, L.N., A. Polycarpou, K. Vrachimis. (2013). Labour Economics. 21: 86-102.

Daczo, Z. (2012). Wage inequality and the gender wage gap: are American women swimming upstream? Dissertation.

Daly, A., A. Kawaguchi, X. Meng, and K. Mumford. (2006). The Gender Wage Gap in Four Countries. The Economic Record. 82(257): 165-176.

Day, C. (2012). Economic Growth, Gender Wage Gap and Fertility Rebound. The Economic Record. 88: 88-99.

Diaz, M.A. and R. Sanchez. (2013). Young workers, marital status and wage gap. Revista de Economia Aplicada. 61: 57-70.

Douglas, J.H. and M.D. Steinberger. (2015). The Sexual Orientation Wage Gap for Racial Minorities. Industrial Relations. 54(1): 50-108.

Dozier, R. (2010). Accumulating Disadvantage: The Growth in the Black-White Wage Gap Among Women. Journal of African American Studies. 14: 279-301.

Edwards, R., D. Evans, and A. Smith. (2006). Wage Negotiations in the Asia Pacific: Does Globalization Increase the Wage Gap? Asia Pacific Business Review. 12(1): 95-108.

Elmelech, Y. and H. Lu. (2004). Race, ethnicity, and the gender poverty gap. Social Science Research. 33: 158-182.

Elmslie, B. and E. Tebaldi. (2014). The Wage Gap against Gay Men: The Leveling of the Playing Field. KYKLOS. 67(3): 330-345.

Fisher, J.D. and C.A. Houseworth. (2012). The reverse wage gap among education White and Black women. Journal of Economic Inequality. 10: 449-470.

Flippen, C.A. (2014). Intersectionality at Work: Determinants of Labor Supply among Immigrant Latinas. Gender & Society. 28(3): 404-434.

Fong, C. (2009). The Nonprofit Wage Differential. Thesis, Georgetown Public Policy Institute.

Franks, T. (2007). Gender and the Wage Gap: Still not equal. Thesis. Wichita State University.

Fryer, R.G., D. Pager, and J.L. Spenkuch. (2013). Racial Disparities in Job Findings and Offered Wages. Journal of Law and Economics. 56(3): 633-689.

Glauber, R. (2008). Race and Gender in Families and at Work: The Fatherhood Wage Premium. Gender and Society. 22(1): 8-30.

Heywood, J.S. and D. Parent. (2012). Performance Pay and the White-Black Wage Gap. Journal of Labor Economics. 30(2): 249-290.

Hirsch, B.T. (2008). 2007 Presidential Address: Wage Gaps Large and Small. Southern Economic Journal. 74(4): 915-933.

Hoyos, R.E., M. Bussolo, and O. Nunez. (2012). Exports, Gender Wage Gaps, and Poverty in Honduras. Oxford Development Studies. 40(4): 533-551.

Hum, D. and W. Simpson. (2000). Closing the Wage Gap: Economic Assimilation of Canadian Immigrants Reconsidered. PCeril. 1(4): 427-441.

Ioakimidis, M. (2012). Gender wage gap and earnings: Predicted by tenure in the Czech Republic. The Journal of Developing Areas. 46(1): 31-43.

Kantola, J. and J. Squires. (2012). From state feminism to market feminism? International Political Science Review. 33(4): 382-400.

Kassenboehmer, S.C. and M.G. Sinning. (2014). Distributional Changes in the Gender Wage Gap. ILR Review. 67(2): 335-

Kemeny, T. and M. Storper. (2012). The sources of urban development: wages, housing, and amenity gaps across American cities. Journal of Regional Science. 52(1): 85-108.

Kennedy, A., E. Nagata, B. Mushenski, and K. Johnson. (2009). Wage Discrimination Based on Gender and Race. The Delta Kappa Gamma Bulletin.

Kerr, C. and R. Walsh. (2014). Racial Wage Disparity in US Cities. Race Soc Probl. 6: 305-327.

Kim, M. (2013). Policies to End the Gender Wage Gap in the United States. Review of Radical Political Economics. 45(3): 278-283.

Kunze, A. (2008). Gender wage gap studies: consistency and decomposition. Empirical Economics. 35: 63-76.

Kunze, A. (2005). The evolution of the gender wage gap. Labour Economics. 12: 73-97.

Levine, L. (2004). The Gender Wage Gap and Pay Equity: Is Comparable Worth the Next Step? Library of Congress.

Liu, A.Y. (2004). Sectoral Gender Wage Gap in Vietnam. Oxford Development Studies. 32(2): 225-239.

Livanos, I. and K. Pouliakas. (2012). Educational segregation and the gender wage gap in Greece. Journal of Economic Studies. 39(5): 554-575.

Lyons, C.J. and B. Pettit. (2011). Compounded Disadvantage: Race, Incarceration, and Wage Growth. Social Pr361.oblems. 58(2): 257-280.

Machin, S. and P.A. Puhani. (2003). Subject of degree and the gender wage differential: evidence from the UK and Germany. Economic Letters. 79: 393-400.

Mangino, W. (2010). Race to College: The “Reverse Gap”. Race Soc Probl. 2: 164-178.

Mason, P.L. (2011). Moments of Disparate Peaks: Race-Gender Wage Gaps Among Mature Persons, 1965-2007. Review of Black Political Economy. 38:1-25.

Maume, D.J. and L. Ruppanner. (2015). State liberalism, female supervisors, and the gender wage gap. Social Science Research. 50: 126-138.

Feminist Discussion Post 1: Feminism, the devaluation of the feminine, and men

(This post is the first in a week long discussion between Lauren and I about feminism. The discussion emerged after Lauren posted a video about why she is not a feminist, to which I wrote an open letter to Lauren in response. Lauren and I then agreed to take part in this call-and-response style discussion, in which we post questions/prompts for one another to reply to. Lauren will post her response on youtube in a day or so, at which time she will also pose a question to me (which I will reply to on this website). You can learn more about the backstory and format of the discussion here, where I also explain my approach to the discussion.)

Hi Lauren,

It was hard to settle on a single question to start with, but I suppose we have a few rounds of this ahead of us, so here goes.

The question I ended up settling on kind of expands on ideas I wrote about in my original reply to you. I’m hoping that you can engage with some of the feminist ideas about masculinity and femininity that I described in my response, and address why you see these ideas as being oppositional to the project of making men’s lives more livable. Before I get to the ultimate question, however, I want to elaborate a little more on what I mean.

One of the main ideas that I tried to convey in my original post is that feminism helps us understand and confront not only the violences and inequalities facing women, but also the problems facing men. I tried to describe this in terms of the ways that gender norms (which feminists challenge), also work to entrench ideas about what it mean to “be a man”. These ideas contribute to some of the deeply harmful conditions in men’s lives, which you raised in your video. Included among these are the expectation of strength, stoicism, and suppression of emotion, which help shape which labor fields men occupy, how men are often taught to respond to emotional distress, and how society responds to them when they fail to fully embody masculine norms (e.g. by being a victim, by being nurturing, by not being the primary breadwinner, etc).

Perhaps another way that I should have described this, is that feminism doesn’t only challenge the way the misogyny devalues women, it also challenges the way that misogyny devalues that which is deemed feminine. (Here is a great article about this from the perspective of a feminist man). Feminists often address the devaluation of the feminine by critiquing, challenging, and breaking open gendered binaries in order to create new possibilities for being and acting in the world. Here is just one example of this:

- Rational/Emotional: The characterization of women as emotional, and thus irrational, goes back for a long time in history. This discourse has played a role in the medical treatment of women (e.g. the invention of female “hysteria”), the treatment of women in science (see Sandra Harding’s work), the lack of recognition of emotions as a site of knowledge (here you see the operation of another gendered binary: objectivity/subjectivity), the way that women are characterized in the work place and when running for public office (e.g. the focus on whether Hillary’s emotions will make her unfit to lead), the exclusion of women from combat, and more. Many women can attest to the ways their expressions of emotion are used to characterize them as “crazy”, and to dismiss their voices and valid arguments about their worlds. This discourse, which treats emotions as feminine, irrational, and undesirable, also in turn makes emotions something that men are taught to suppress. This disregard for emotion impacts how men are expected to behave, to deal with emotional, psychological and physical injury, to interact with others, and to labor in their jobs. The fact is, however, that men are emotional, men need emotions, and this feminization and devaluation of emotions hurts men.

There are many more of these binaries that feminists challenge, including: man/woman, productive/reproductive, objectivity/subjectivity, rational/emotional, mind/body, public/private, political/personal, culture/nature, active/passive, perpetrator/victim, protector/protected, and global/local. I could elaborate a lot about this, but for the sake of brevity, hopefully you can go back and see where I already allude to these in my previous post (e.g. productive/reproductive in terms of breadwinning and caregiving; feminists challenging victim/perpetrator narratives). If you want, I’d be happy to elaborate more on this in another post.

The point I’m trying to make is that when feminists fight for the revaluation of the feminine and for the breaking down of these binaries, they are also opening up terrain for men to express emotion, to buck norms of masculinity that route them towards harm, to claim a role in childrearing, and to be treated fairly when they are victimized. Even the very binary of male/female can be broken open when we examine (as feminists like Judith Butler do) how the presumably natural characteristics of sex and gender are in fact deeply social, and thus open to change.

So, all this build-up was to set up this related set of questions:

With so many of the harms you point to in your video being fundamentally shaped by the very gendered binaries that feminists challenge, why don’t you see feminism as a project that improves men’s lives? Don’t you agree that a project that challenges the devaluation of femininity would also help to address many of the harms men face? Wouldn’t it be more beneficial to look to feminists as allies rather than opponents?

Now here, I just want to note that the topic of how to be an ally and how to act in solidarity is already really prevalent in feminist activist and scholar communities. The role of white people in on-going Black Lives Matter protests is just one example of the continued need to engage in discussions about solidarity and voice, and feminists (and particularly feminists of color) are active in these debates. Feminists often talk and debate on issues of how to create solidarity across difference and how to hold each other accountable in being better allies. When feminists challenge one another to be better allies, however, it’s usually premised on improving a movement that is already so deeply invested in equality and which already has so many tools to understand and confront the ways that power operates through gender, race, class, and sexuality. In this regard, I’ll agree there is room to talk about improving feminist allyship for men experiencing particular harms (male rape victims being a good example). This is not to say there aren’t feminists doing this work though, because, as I have argued, there are many feminists speaking on issues affecting men. Your assertion that feminists are silent is unfair and inaccurate. There is always room to improve though, and discussion and critique is undoubtedly part of how feminists challenge each other to do so. In fact, talking about this would be deeply in line with existing internal debates about allyship among feminists. In these discussions, feminists may also have some very valid questions about how men’s rights groups act (or don’t act) as allies to them as well, and they might point out the stakes for women when men’s groups dismiss, diminish, deny, and derail real valid struggles to improve women’s lives. So, maybe the real heart of the issue is: How can we improve allyship and build solidarity between feminists and men (who may or may not be feminists themselves)? How can we do this without disregarding or ignoring the real and powerful work feminists are already doing? And, how can we do this without dismissing feminism itself, which (I really hope you see) presents so many tools for addressing the harms done by restrictive gender norms?

I know that’s more than one question, but I hope it makes sense why I place them together. I look forward to hearing your first response.

All the best,

Jenna

ANNOUNCEMENT: An Upcoming Virtual Discussion with Lauren Southern

Hi all,

So, a couple weeks ago, I wrote a blog post in reply to Lauren Southern’s viral video “Why I’m Not a Feminist”. I initially wrote this thinking it would be read by a few feminist friends, and I was shocked (and grateful!) by how widely it ended up getting circulated. To date, it has had over 75,000 views, which is totally wild. Trust me, it is a rare experience as a graduate student to have so many people read and engage with something I’ve written, so thank you. I have loved hearing from many of you in the comments section of the blog, in emails, and on reddit forums. I have also learned a lot from your replies—about cool feminist projects, about concerns and conceptions people have about feminism, and about some of the challenges of communicating feminist ideas to a mass audience. More than anything, I’ve really appreciated how thoughtfully most people have participated in the discussion, including those who thoroughly disagreed with what I was saying.

Anyway, yesterday I head from Lauren via Twitter.

After we discussed it a little bit, we agreed on the following:

We would do a one-week call-and-response style online discussion, in which we’ll post questions/prompts for one another. The person will have a day or two to offer a response and to post a new question/prompt for the other person. Lauren will use youtube for her replies, and I’ll use my blog.

Now, I’ll confess this is a nerve-wracking for me.

My first, and perhaps most obvious, concern is that feminism is such a huge arena of activism, ideas, and scholarship. It’s incredibly heterogeneous, and I certainly do not want to remotely claim that I am an expert on every arena of feminist thought and action. Moreover, I want to be really, really clear that I do not represent all feminists. Feminists debate and critique each other’s work all the time. It’s part of what keeps the movement changing, and part of how we push each other to improve. Given this breadth, when I write my replies, I will undoubtedly need to turn to other feminists to learn about topics I’m less well versed in. On this note, I’m all for crowd sourcing some help, so feminists who are following the discussion should feel free to send me sources that might help me address Lauren’s questions. I’m grateful for whatever insights you can add. You can email them to me at everydaygeopoliticshouston@gmail.com.

My second concern about doing this discussion is that this will be a debate between two white cis-gender women. Within feminist history, there is a long, problematic, and on-going history of white feminists bogarting the mic, speaking for all women, and focusing on liberal feminist projects that tend to benefit largely white women, while neglecting issues of LGBTQ people and people of color. This concern feels particularly ripe at this current moment given the need to maintain support and momentum for movements like Black Lives Matter. This week, I think it is more important to talk about what happened to Rekia Boyd, who was killed by an off-duty cop while walking, unarmed, with her friends, than it is to talk about the wage-gap. The man who killed her was just acquitted by some truly insane courtroom logic, and too-few people are standing up. I hope Lauren and I will be able to talk about these issues in relation to feminism. Given that she’s Canadian, perhaps we could also put #BlackLivesMatter into conversation with #AmINext and the issue of missing and murdered indigenous women in Canada. Anyway, I’ll also do my best to keep these issues (and the voices of queer feminists and women of color) front and center here. I do welcome ideas on ways to improve how I do this though, both in terms of formatting (perhaps a way to include more voices in the reply?) and in terms of the content I write and the questions I pose to Lauren. Again, feel free to reach out to me.

My last concern is that the discussion will turn overly adversarial. Both Lauren and I agree we don’t want this, and we hope that those who join in the conversation will try to be respectful to both of us along the way. These can be complicated and difficult conversations to have, all the more so when they’re done in front of thousands of people. So, let’s all try to keep the conversation going productively. That said, we do hope you join in in, and feel free to share thoughts with us in the comment sections of my blog and her video, on Twitter (although, I myself am less of an active Twitter-user), or via email.

I’ll be posting the first question for Lauren tomorrow. So check back soon!

All the best,

Jenna

A Bibliography of Houston

**Thank you to all you have commented or emailed me with resources, books and articles to add to this list!**

As a number of scholars have noted, there is comparatively less scholarship about the Houston compared to other U.S. cities of its size and significance, particularly when it comes to contemporary research (as I’ve come to see there is quite a wealth of historical work that’s been done). Anyway, given that I’m working on research down here, I’ve been collecting whatever I can find about Houston politics, history, and culture. I wanted to share what I’m finding with you so that others also access all these resources in one spot, and in the hopes that others might be able to add to this list. I’ll try to include a blurb about all of the books (not articles though). Feel free to get in touch with me if you know of other things to add to this list. I’ll treat this as a living document and continue to add things to it, so continue to check back!

Books:

Bazaldua, M. (2007). Thanks to Prison: Operation State Boots to Gucci Boots. Houston: Maroon Publishing.

Bazaldua, M. (2007). Thanks to Prison: Operation State Boots to Gucci Boots. Houston: Maroon Publishing.

Autobiographical story of Bazaldua, who grew up in Houston, and his experiences in the criminal justice system and beyond.

Beeth, H. and C.D. Wintz. (1992). Black Dixie: Afro-Texan History and Culture in Houston. College Station, TX: Texas A & M University Press.

An innovative contribution to the growing body of research about urban African-American culture in the South, Black Dixie is the first anthology to track the black experience in a single southern city across the entire slavery/post-slavery continuum. It combines the best previously published scholarship about black Houston and little-known contemporary eyewitness accounts of the city with fresh, unpublished essays by historians and social scientists.

Divided into four sections, the book covers a broad range of both time and subjects. The first section analyzes the development of scholarly consciousness and interest in the history of black Houston; slavery in nineteenth-century Houston is covered in the second section; economic and social development in Houston in the era of segregation are looked at in the third section; and segregation, violence, and civil rights in twentieth-century Houston are dealt with in the final section.

Beste, P., L.S. Walker, J. Kugelberg, Bun B. (2013). Houston Rap. New York: Sinecure.

“The Houston, Texas Neighborhoods of Fifth Ward, Third Ward, and South Park have grown to be hallowed ground for modern rap culture, possessing self-contained celebrities, entrepreneurs, support networks, and a micro-economy of their own…Photographer Peter Beste and writer Lance Scott Walker spent nine years documenting the most influential style in 21st century hip-hop and the vibrant inner city culture from which it stems… Houston Rap, edited by Johan Kugelberg, profiles noted artists such as Bun B of UGK, Z-Ro, Big Mike, K-Rino, Willie D of the Geto Boys, Lil’ Troy, and Paul Wall, alongside reflections of the lives of departed legends such as DJ Screw, Pimp C, and Big Hawk.”

“The Houston, Texas Neighborhoods of Fifth Ward, Third Ward, and South Park have grown to be hallowed ground for modern rap culture, possessing self-contained celebrities, entrepreneurs, support networks, and a micro-economy of their own…Photographer Peter Beste and writer Lance Scott Walker spent nine years documenting the most influential style in 21st century hip-hop and the vibrant inner city culture from which it stems… Houston Rap, edited by Johan Kugelberg, profiles noted artists such as Bun B of UGK, Z-Ro, Big Mike, K-Rino, Willie D of the Geto Boys, Lil’ Troy, and Paul Wall, alongside reflections of the lives of departed legends such as DJ Screw, Pimp C, and Big Hawk.”

Walker, Lance Scott, Johan Kugelberg, Michael Daley, Peter Beste, and Willie D. (2013). Houston Rap Tapes. Los Angeles, CA: Sinecure Books.

Walker, Lance Scott, Johan Kugelberg, Michael Daley, Peter Beste, and Willie D. (2013). Houston Rap Tapes. Los Angeles, CA: Sinecure Books.

Houston Rap Tapes is the companion to Houston Rap, Peter Beste’s intimate photo book on this important hip hop culture.Houston Rap Tapes complements Beste’s photography with a series of oral histories conducted by writer Lance Scott Walker. The book features exclusive interviews with legendary producers and MCs such as Bun B, Willie D, Paul Wall, Z-Ro, Big Mike, DJ DMD, K-Rino, Salih Williams and Lil’ Troy, alongside stories from old school masters like MC Wickett Crickett and Rick Royal. The life stories of the Houston rap scene are also represented by an assortment of radio and club personalities, impresarios, ex-pimps, former drug dealers and members of the community. Lance Scott Walker and Peter Beste spent nine years documenting the most influential style in twenty-first-century hip hop and the vibrant inner-city culture from which it stems.

Bullard, R. (1987). Invisible Houston: The Black Experience in Boom and Bust. College Station: Texas A&M University Press.

In this book, Robert Bullard, when of the foremost scholars of environmental racism, “systematically explores the demographic, social, economic, and political factors that helped make Houston the “golden buckle” of the Sunbelt. He then chronicles the rise of Houston’s black neighborhoods, the first of these being the settlement of emancipated slaves in Freedmen’s Town, an area which is the site of the present-day Forth Ward. Bullard analyzes the boom era of the 1970s and the dwindling economy and government commitment to affirmative action in the 1980s. Using case studies conducted in Houston’s Third Ward, the city’s most diverse black neighborhood and a microcosm of the larger black Houston community, he presents data on and discusses housing patterns, discrimination, pollution, law enforcement, and leadership, relating these issues to the larger ones of institutional racism, poverty, and politics.” Still so relevant to Houston today.

Center for Land Use Interpretation in Houston. (2009). On the Banks of Bayou City. Blaffer Gallery, Art Museum of the University of Houston.

Since 1994, The Center for Land Use Interpretation (CLUI)–a research organization based in Culver City, California–has studied the U.S. landscape, using multidisciplinary research, information processing and interpretive tools to stimulate thought and discussion around contemporary land-use issues. During a residency at the University of Houston Cynthia Woods Mitchell Center for the Arts, the CLUI established a field station on the banks of the Buffalo Bayou, revealing aspects of the relationship between oil and the landscape in Houston that are often overlooked–even by the city’s residents. The CLUI’s findings are presented in this volume and a concurrent exhibition at the Blaffer Gallery, titled Texas Oil: Landscape of an Industry. The book documents the CLUI’s methodology in a series of interviews and includes a photographic essay on land use in Houston featuring a panoramic, foldout section and a comprehensive chronology of the CLUI’s projects and publications over the past 14 years.

Cole, Thomas R. (1997). No Color Is My Kind: The Life of Eldrewey Stearns and the Integration of Houston. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

Cole, Thomas R. (1997). No Color Is My Kind: The Life of Eldrewey Stearns and the Integration of Houston. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

“No Color Is My Kind is an uncommon chronicle of identity, fate, and compassion as two men—one Jewish and one African American—set out to rediscover a life lost to manic depression and alcoholism. In 1984, Thomas Cole discovered Eldrewey Stearns in a Galveston psychiatric hospital. Stearns, a fifty-two-year-old black man, complained that although he felt very important, no one understood him. Over the course of the next decade, Cole and Stearns, in a tumultuous and often painful collaboration, recovered Stearns’ life before his slide into madness—as a young boy in Galveston and San Augustine and as a civil rights leader and lawyer who sparked Houston’s desegregation movement between 1959 and 1963.

While other southern cities rocked with violence, Houston integrated its public accommodations peacefully. In these pages appear figures such as Thurgood Marshall, Martin Luther King, Jr., Leon Jaworski, and Dan Rather, all of whom—along with Stearns—maneuvered and conspired to integrate the city quickly and calmly. Weaving the tragic story of a charismatic and deeply troubled leader into the record of a major historic event, Cole also explores his emotionally charged collaboration with Stearns. Their poignant relationship sheds powerful and healing light on contemporary race relations in America, and especially on issues of power, authority, and mental illness.

De León, Arnoldo (2001). Ethnicity in the Sunbelt: Mexican Americans in Houston. Houston, Texas: University of Houston, Center for Mexican American Studies.

De León, Arnoldo (2001). Ethnicity in the Sunbelt: Mexican Americans in Houston. Houston, Texas: University of Houston, Center for Mexican American Studies.

A century after the first wave of Hispanic settlement in Houston, the city has come to be known as the “Hispanic mecca of Texas.” Arnoldo De León’s classic study of Hispanic Houston, now updated to cover recent developments and encompass a decade of additional scholarship, showcases the urban experience for Sunbelt Mexican Americans.

De León focuses on the development of the barrios in Texas’ largest city from the 1920s to the present. Following the generational model, he explores issues of acculturation and identity formation across political and social eras. This contribution to community studies, urban history, and ethnic studies was originally published in 1989 by the Center for Mexican American Studies at the University of Houston. With the Center’s cooperation, it is now available again for a new generation of scholars.

Fenberg, S. (2013). Unprecedented Power: Jesse Jones, Capitalism, and the Common Good. College Station, Texas: Texas A&M University Press.

“Unprecedented Power shows how Jesse Jones and the Reconstruction Finance Corporation restored the economy during the Great Depression, built massive, cutting-edge industries in time for the Allied Forces to fight and win World War II and made money for the federal government at the same time. No wonder Kirkus Reviews said Unprecedented Power “holds enormous relevance today.” Next to President Roosevelt, Jesse Jones was considered to be the most powerful person in the nation throughout the Great Depression and World War II. Largely forgotten today, he helped define Franklin Roosevelt’s presidency as one that in many instances provided positive, profound and enduring results for the nation in a financially astute and responsible manner. Jesse Jones’s successful efforts and methods to preserve capitalism and democracy during two of the most tumultuous and dangerous periods in United States history deserve attention today. According to author Steven Fenberg, Jones understood he would prosper only if his community thrived, a belief that directed him to combine capitalism and public service to develop his hometown of Houston, to rescue his country and to save nations. As we grapple with the role of government, unemployment, financial insecurity for many, crumbling infrastructure and reliance on other nations for vital resources, Unprecedented Power offers models for today by looking at successes from the past.”

Fairbanks, R.B. (2014). The War on Slums in the Southwest: Public Housing and Slum Clearance in Texas, Arizona, and New Mexico, 1935-1965. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

In The War on Slums in the Southwest, Robert Fairbanks provides compelling and probing case studies of economic problems and public housing plights in Albuquerque, Dallas, Houston, Phoenix and San Antonio. He provides brief histories of each city–all of which expanded dynamically between 1935 and 1965–and how they responded to slums under the Housing Acts of 1937, 1949, and 1954.

Despite being a region where conservative politics has ruled, these Southwestern cities often handled population growth, urban planning, and economic development in ways that closely followed the national account of efforts to eliminate slums and provide public housing for the needy. The War on Slums in the Southwest therefore corrects some misconceptions about the role of slum clearance and public housing in this region as Fairbanks integrates urban policy into the larger understanding of federal and state-based housing policies.

Faniel, M.L. (2013). Hip-Hop in Houston: The Origin & The Legacy. Charleston: The History Press.

Faniel, M.L. (2013). Hip-Hop in Houston: The Origin & The Legacy. Charleston: The History Press.

“Rap-A-Lot Records, U.G.K (Pimp C and Bun B), Paul Wall, Beyonce, Chamillionaire and Scarface are all names synonymous with contemporary hip-hop. And they have one thing in common: Houston. Long before the country came to know the chopped and screwed style of rape from the Bayou Country in the late 1990s, hip-hop in Houston grew steadily and produced some of the most prolific independent artists in the industry. With early roots in jazz, blues, R&B and zydeco, Houston hip-hop evolved not only as a musical form but also as a cultural movement. Join Maco L. Faniel as he uncovers the early years of Houston hip-hop from the music to the culture it inspired.”

Feagin, J. (1998). Free Enterprise City. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.